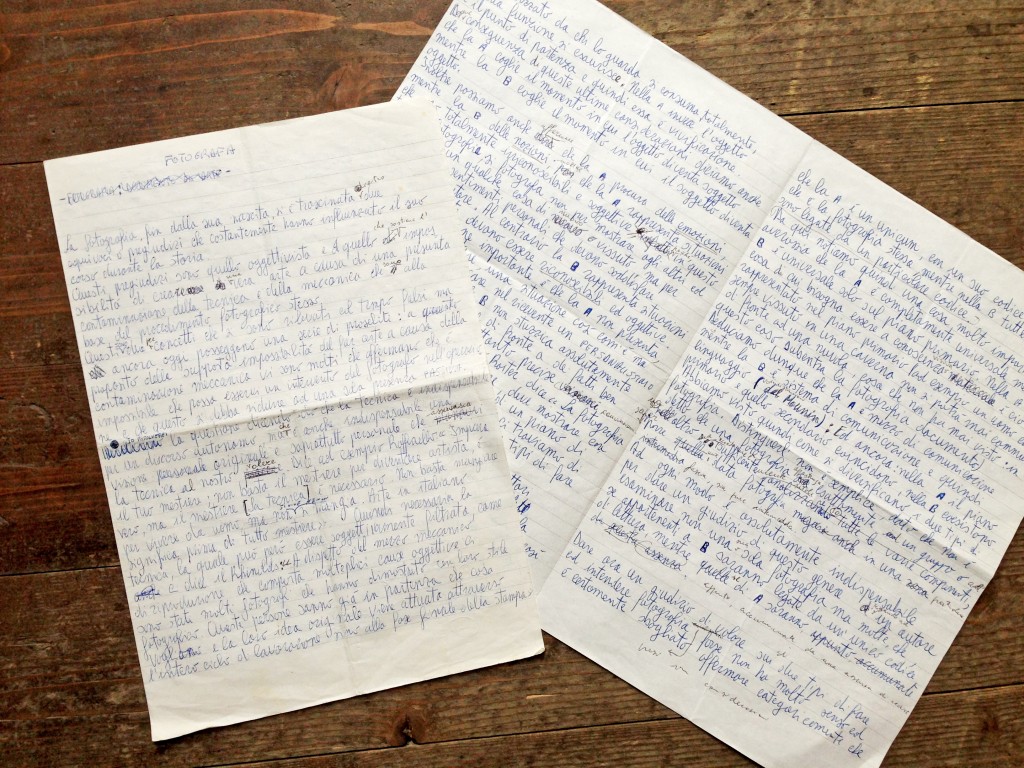

non so bene quanti anni avessi, non è datato, ma secondo me ero al ginnasio, quindi 15/16 anni. forse 17.

l’abbiamo “decifrato” e trascritto.

eccolo qui:

La fotografia, fin dalla sua nascita, si è trascinata dentro due equivoci o pregiudizi che costantemente hanno influenzato il suo corso durante la storia.

Questi pregiudizi sono quello oggettivista e quello che sostiene l’impossibilità di creare una vera arte a causa di una presunta contaminazione della tecnica e della meccanica che sono alla base del procedimento fotografico stesso.

Questi sono due preconcetti che si sono rivelati con il tempo falsi ma ancora oggi posseggono una serie di proseliti: a proposito della supposta impossibilità del fare arte a causa della contaminazione meccanica vi sono molti che affermano che è impossibile che possa esservi un intervento del fotografo nell’operazione e che questo si debba ridurre ad una sola presenza passiva.

Io risolverei la questione dicendo solo che la tecnica è indispensabile per un discorso autonomo, ma che è anche indispensabile una visione originale e soprattutto personale che asservisca la tecnica al nostro volere.

Dice ad esempio Raffaello “Impara il tuo mestiere; non basta il mestiere per diventare artista, è vero, ma il mestiere [la tecnica] è necessario. Non basta mangiare per vivere da uomo, ma non si vive se non si mangia. Arte in italiano significa prima di tutto mestiere”.

Quindi necessaria la tecnica, la quale può però essere soggettivamente filtrata, come ci dice Rinholds: “ A dispetto del mezzo meccanico di riproduzione che comporta molteplici cause oggettive, ci sono stati molti fotografi che hanno dimostrato un loro stile fotografico. Queste persone sanno già in partenza che cosa vogliono e la loro idea originale viene attuata attraverso l’intero ciclo lavorativo sino alla fase finale della stampa.”

Questo primo pregiudizio che ho brevemente analizzato effettivamente può essere riscontrato quando ci si trova di fronte a certo stupido fotoamatorismo, davanti ad una situazione cioè che vede veramente il fotografo asservito a certe tentazioni di virtuosismo tecnico che lo allontanano dalle sue vere e personali aspirazioni.

A proposito dell’oggettività della fotografia il problema si fa più complesso e coinvolge un po’ tutto l’andamento che la fotografia ha avuto nella sua esistenza.

Infatti “oggettivo” può stare anche per “fedele” e questo sillogismo ha portato a molti fraintendimenti non solo nel campo fotogiornalistico ma anche in quello artistico. Infatti la maggior parte della gente ha sempre pensato, coscientemente o più spesso incoscientemente “La fotografia è oggettiva, quindi è fedele al reale e quindi tutto ciò che vedo in fotografia è esistito esattamente come è nella fotografia”.

Questo pregiudizio nei riguardi della fotografia fu particolarmente sentito all’epoca della sua nascita e in tutto il 1800 mentre nel nostro secolo ha avuto in più uno spostamento di piano decisivo entrando nei limiti della cosiddetta fotografia artistica.

Mi spiego meglio: appena nata la fotografia stupì immensamente per la sua capacità (supposta) di far vedere il reale così come appare. Infatti la fotografia trovò le sue prime applicazioni pratiche oltre che nella ritrattistica, che ha una sua particolare motivazione sociale, non tanto nel reportage quanto invece nel documento: il documento esotico di fatti, di posti sconosciuti o lontani.

Vediamo quindi ad esempio O’Sullivan girovagare per l’America per mostrarne gli aspetti più particolari e curiosi, come anche W. H. Jackson o R. Fenton fotografare la guerra di Crimea o vari fotografi partire dall’Europa per esplorare le lontane terre orientali o le meraviglie dell’Egitto.

Le fotografie che questi fotografi portarono in patria stupirono l’opinione pubblica che ancora più si convinse delle miracolose potenzialità della fotografia: questa convinzione si sviluppò in una corrente di pensiero che è viva ancora ai giorni nostri e che vorrebbe la fotografia unicamente come documento della realtà. Della nostra vita.

Tutti gli studi di critica ormai insistono solo su questo: esempio paradigmatico è la critica americana S. Sontag che fa di questo pensiero le sue basi.

Anche la fotografia cosiddetta artistica e quella non fatta sotto precise committenze viene analizzata come sottoposta a questo canone e grandi fotografi sono analizzati unicamente come documentaristi.

Questo concetto conduce la Sontag a delle considerazioni sociologiche che non ritengo possano essere valide per qualsiasi tipo di fotografia: ecco ad esempio cosa scrive nel suo saggio “Sulla fotografia”: “Ogni fotografia è memento mori. Fare una fotografia significa partecipare alla mortalità, alla vulnerabilità ed alla mutabilità di un’altra cosa o persona” e ancora “guardare una fotografia significa per prima cosa pensare: quanto più giovane ero (o era) allora. La fotografia è l’inventario della mortalità. Basta un movimento del dito per conferire ad un momento un’ironia postuma. Le fotografie mostrano persone che sono lì ad un’età specifica della loro vita”. Oppure afferma che la fotografia è dare una prevalenza, un’importanza a qualche cosa rispetto ad un’altra.

Tutto ciò è vero, assolutamente vero, ma, attenzione, solo per un tipo di fotografia (che è poi il più diffuso a tutti i livelli): quello di una fotografia fatta per stupirsi nella sua contemplazione e ,soprattutto, per stupire gli altri; quello di una fotografia bella, piacevole a vedersi, ma tutto ciò in modo passivo e non attivo perché bella e piacevole non sarà la fotografia in sé per sé, ma l’oggetto fotografato (concetto questo ben accennato anche dal Turroni nel suo saggio “Guida alla critica fotografica”).

Il normale e tranquillo fotoamatore fotografa non tanto per esprimere sue le sue vere pulsioni interiori, ma quanto per avere una testimonianza decisiva e sicura della sua visione di un dato fatto o di una certa cosa. E così passa in dieci minuti dal fotografare tramonti rosso fuoco al fotografare vecchiette con “tante belle rughe”: tutte cose che non sono legate se non dalla volontà di stupirsi e di stupire del fotografo.

Esiste però un’altra fotografia, molto diversa da quella analizzata dalla Sontag . Anzi completamente opposta. E’ la fotografia che possiamo veramente dire aver inventato il grandissimo A. Stieglitz, il fotografo americano vissuto nei primi del ‘900. Egli creò il concetto degli “equivalents” che non solo appunto portò ad una fotografia originale ma anche ad un nuovo modo totale di concepire e fare fotografia.

Il concetto degli “equivalents” è semplice: quando Stieglitz, ad esempio, fotografava delle nuvole, quelle nuvole per lui non erano il punto di chiusura della sua indagine fotografica ma quello di partenza, dato che esse rappresentavano un qualche cosa di diverso, astratto, su un altro piano.

La fotografia così diventò vera espressione, vera potenzialità, attiva e creativa, vero strumento di indagine, possiamo anche dire, filosofica.

Stieglitz infatti ad esempio disse: “Sono nato ad Halsocken. Sono americano. La fotografia è la mia passione. La ricerca della verità la mia ossessione”.

Il Nostro in questo si avvicina molto anche alla pittura e infatti nella sua galleria, la “291”, introduce le avanguardie pittoriche del suo tempo.

La fotografia di Stieglitz è quella contro la quale si getta la Sontag la quale, sempre nel suo saggio “Sulla fotografia” parlando di Evans scrive: “Evans voleva che le sue fotografie fossero colte, autorevoli e trascendenti. Ma poiché l’universo morale degli anni trenta non è più il nostro, questi aggettivi oggi sono quasi incredibili. Nessuno riesce ad immaginare come potrebbe la fotografia essere autorevole. Nessuno chiede più che essa sia colta. Nessuno capisce più come una cosa qualunque, e tanto meno una fotografia, possa essere trascendente….”

Si vengono quindi proprio a creare due tipi distinti di fotografia una, diciamo così, artistica e l’altra documentaristica.

Questa divisione però spesso non si fa in base a precisi schemi mentre quello che vorrei io fare è proprio dare degli schemi quasi scientifici, per differenziare in modo netto i due settori. Per rendere ciò più snello chiamiamo la prima fotografia artistica A, mentre la seconda, quella documentaristica B.

Come divisione sostanziale cominciamo a dire che la A è l’espressione pura dei sentimenti e delle passioni umane, mentre la B è documento di situazioni. Se qualcuno mi dicesse che anche nella B si possono intravedere i sentimenti dell’autore delle fotografie, io risponderei a queste obiezioni osservando che tali sentimenti sono sì scopribili e avvertibili ma solo di riflesso a causa della maniera, della tecnica in cui il fotografo ha fotografato e quindi interpretato una data situazione, ma non è genuina espressione, è critica!

Procedendo, diremo che la B è uccisione dell’oggetto fotografato (come pure sostiene R. Barthers) perché esso una volta fotografato e analizzato da chi lo guarda si consuma totalmente, la sua funzione si esaurisce.

Nella A invece l’oggetto è il punto di partenza e quindi essa è vivificazione.

Come conseguenza di queste ultime considerazioni diciamo anche che la A coglie il momento in cui l’oggetto diventa soggetto mentre la B coglie il momento in cui il soggetto diventa l’oggetto.

Inoltre possiamo anche affermare che la A procura delle emozioni mentre la B delle nozioni; inoltre che la A rappresenta situazioni che sono totalmente irriconoscibili e soggettive poiché in questo tipo di fotografia si fotografa non per mostrare agli altri e a se stessi un qualche cosa di nuovo o vissuto, ma per esprimere dei sentimenti personali che devono soddisfare unicamente l’autore. Al contrario la B rappresenta situazioni che necessariamente devono essere riconoscibili ed oggettive.

Un’altra considerazione importante è che la A non presenta e non deve presentare una situazione così com’è ma stuzzica, allude per innescare nel ricevente un PERSONALISSIMO atto di EMOZIONE. Invece la B non stuzzica assolutamente ma strappa delle decisioni, pone difronte a dei fatti ben precisi che ci dispongono in altrettanto precise convinzioni.

Su questo punto ad esempio Fulvio Roiter dice “la fotografia non deve alludere, non deve suggerire, deve mostrare con chiarezza”.

Se ci spostiamo ora su di un piano di analisi linguistica anche in questo caso ci troviamo di fronte a differenze sostanziali tra i due tipi di fare fotografia. Innanzitutto diciamo che la B è legata a fattori extrafotografici (linguaggio, cultura ecc) che ne influenzano profondamente la lettura, mentre la A contiene tutte le unità morfologiche. Si deduce così che la A è un unicum, con un suo codice particolare, che è la fotografia stessa, mentre nella B tutte le fotografie di uno stesso cielo sono legate ad un particolare codice. Da qui notiamo quindi una cosa molto importante ovverossia che la A è completamente universale mentre la b è universale solo sul piano primario. Nella A l’unica cosa di cui bisogna essere a conoscenza visiva è ciò che è rappresentato nel piano primario (ad esempio un uomo che è sempre vissuto in una caverna non si potrà mai commuovere di fronte ad una nuvola, cosa che non ha mai visto: in questo caso subentra la fotografia documento).

Deduciamo dunque che la A è mezzo di comunicazione mentre la B è sistema di comunicazione e quindi linguaggio (vedi distinzioni del Mounin). E ancora nella A il piano primario e quello secondario coincidono, nella B coesistono.

Abbiamo visto quindi come si diversificano i due tipi di fotografia. Distinguerli non è semplice, dato che non è detto che una fotografia appartenga esattamente ad un gruppo o all’altro e secondo me è sufficientemente inutile analizzarlo per porre una data fotografia in una particolare fascia, sia pure intermedia.

Ad ogni modo è assolutamente indispensabile per dare un giudizio di questo genere riguardo ad un autore esaminare non una sola fotografia ma molte che se appartenenti a B saranno legate da un unico codice di lettura, mentre se di A saranno appunto accumunate da un’ assenza di codice.

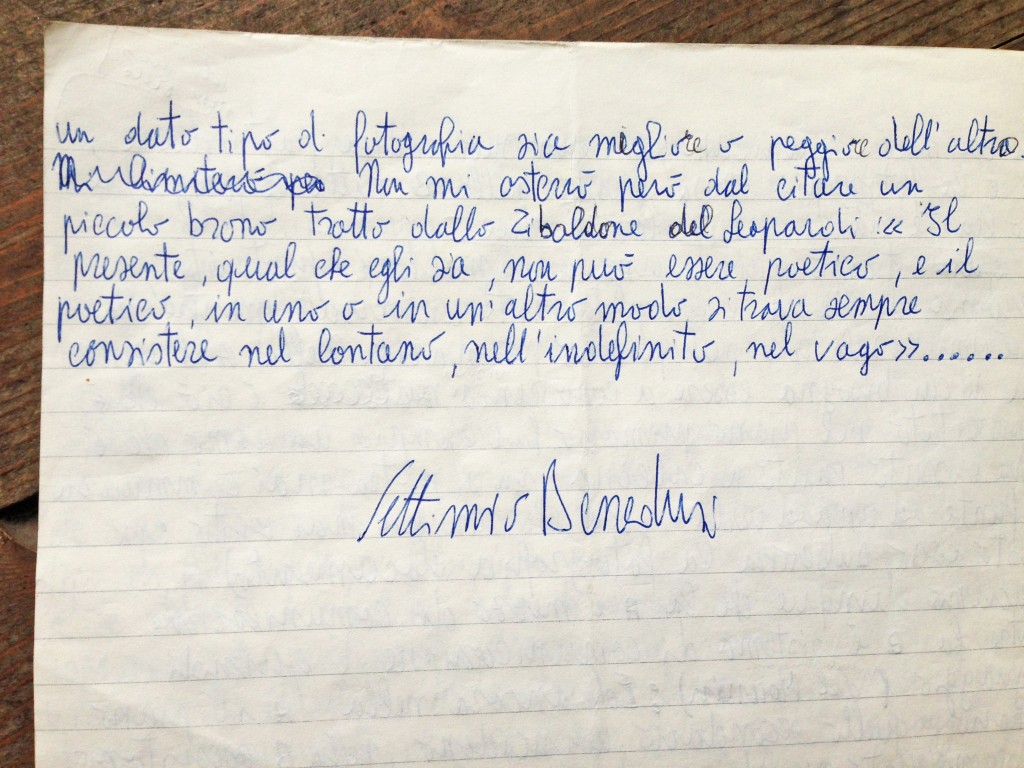

Dare ora un giudizio di valore sui due tipi di fare e intendere fotografia presi in considerazione forse non ha molto senso, ed è certamente sbagliato affermare categoricamente che un dato tipo di fotografia sia migliore o peggiore dell’altro.

Non mi asterrò però dal citare un piccolo brano tratto dallo Zibaldone di Leopardi: “Il presente, qual che egli sia, non può essere poetico, e il poetico, in uno o nell’altro modo si trova sempre consistere nel lontano, nell’indefinito, nel vago”… [/it]

[en]

I found, at the bottom of a drawer of youth, an execution (it was a free theme I suppose) whose title was “ photography: document or art”.

I am not sure how old I was, it doesn’t have a date, but I was at the gymnasium, so 15/16 years old. perhaps 17.

we have “deciphered” and transcribed it.

here it is:

Photography, since its inception, has been drawn into two misunderstandings or prejudices that constantly influenced its course throughout history.

These misconceptions are the objectivism and what claims to be impossible to create a true art because of an alleged contamination of the technique and mechanics that are the basis of the photographic process itself.

These are two assumptions that have proven false over time but still possess a number of proselytes: about the supposed impossibility of making art because of mechanical contamination there are many who say it is impossible that there must be an intervention by the photographer in the process and that this must be reduced to a single passive presence.

I would answer the question by saying only that the technique is essential for an autonomous discourse, but it is also essential to an original vision and above all personal that would serve technology to our will.

For example, Raffaello says “Learn your craft, the trade is not enough to become an artist, it is true, but the trade [the technique] is necessary. Do not just eat to live as a man, but you can not live if you do not eat. Art in Italian means first of all trade”.

Therefore the technique is necessary, which may however be subjectively filtered as Rinholds tells it: “In spite of the mechanical means of reproduction involving a number of objective reasons, there were many photographers who have shown their photographic style. These people already know what they want and leaving their original idea is carried through the entire life-cycle until the final stage of printing.”

This first prejudice that I have briefly analysed actually can be found when you are in front of certain stupid photo amateurialism, faced with a situation that you really see the photographer interlocked with certain temptations of technical virtuosity that lead him away from his real and personal aspirations.

About the objectivity of photography the problem is more complex and involves all the progress that photography has had in its existence.

In fact, “objective” can stand for “faithful” and this syllogism has led to many misunderstandings not only in the photojournalistic field but also in the artistic one. In fact, most people have always thought, consciously or more often unconsciously “photography is objective, and is faithful to reality and so all you see in the picture is exactly as it existed in the photograph.”

This bias towards photography was particularly felt at the time of its birth and throughout the 1800s while in our century it has had more than one floor decisive move coming within the limits of the so-called artistic photography.

Let me explain it better: as photography was born it surprised immensely with its ability (supposed) to see the reality as it appears. In fact, the picture found its first practical applications as well as in portraiture, which has its own particular social motivation, not so much in reportage but in the document: the exotic document of facts, unknown or far away places.

Thus we see, for example O’Sullivan wander in America to show the most peculiar and curious aspects, as well as W. H. Jackson or R. Fenton photographing the Crimean War or various photographers from Europe to explore the far eastern lands or the wonders of Egypt.

The photographs these photographers brought home amazed the public that became even more convinced of the miraculous power of pictures: this belief developed into a school of thought that is still alive today and would like the photograph only as a document of reality. Of our lives.

All studies critics now insist only on this: paradigmatic example is the American critic S. Sontag that makes this thought her bases.

Even the so-called artistic photograph and the one not taken under precise commissions is analysed as if subjected to this standard and great photographers are analysed solely as documentary filmmakers.

This concept leads Sontag to sociological considerations that I think can not be valid for any type of photography: here is an example of what she writes in her essay “On Photography”: “Each photograph is a memento mori. To take a photograph is to participate in mortality, vulnerability and mutability of another person or thing “and still” looking at a photograph means first think how much younger I was (or it was) then. Photography is the inventory of mortality. Just a flick of the finger to grant a moment posthumous irony. The photographs show people who are there for a specific age in their lives”. Or it confirms that photography is giving a prevalence, an importance to something over another.

All this is true, absolutely true, but be careful, only for one type of photography (which is the most widespread at all levels): a photograph taken to astonish in its contemplation and, above all, to astonish others; the beautiful picture, nice to look at, but everything in a passive and not active because the photograph won’t be pleasant and beautiful per se, but the object photographed (concept also well mentioned by Turroni in his essay “Guide the photographic criticism “).

The normal and calm amateur photographer photographs not so much to express his true inner drive, but to have a safe and decisive witness of his vision of a given fact or a certain something. And so in ten minutes he’ll go from shooting fiery red sunsets to photographing old ladies with “many fine wrinkles”: all things that are not related if not by the desire to surprise and amaze the photographer.

But there is another photography, very different from that analysed by Sontag. In fact the complete opposite. Its the photograph that we can truly say that the great A. Stieglitz invented, the American photographer who lived in the early ‘900. He created the concept of “equivalents” that not only precisely led to an original photo but also to a total new way of thinking and doing photography.

The concept of “equivalents” is simple: when Stieglitz, for example, was photographing clouds, those clouds were not for him the closing point of his photographic investigation but the beginning, since they represented something different, abstract, on another level.

The photograph became true expression, true potential, active and creative, real investigative tool, we can also say, philosophical.

Stieglitz fact, for example, said: “I was born in Halsocken. I’m an American. Photography is my passion. The search for truth my obsession. “

Our in this is very similar to painting in fact in his own gallery, the “291”, introduces the avant-garde painting of his time.

Stieglitz’s photography is the one on which Sontag throws herself onto who, always in her essay “On Photography” talking about Evans writes: “Evans wanted his photographs were cultured, authoritative, and transcendent. But since the moral universe of the thirties is no longer ours, today these adjectives are almost unbelievable. No one can imagine how a picture can be authoritative. No one asks anymore for it to be cultured. No one understands anymore how anything, let alone a photograph, can be transcendent …. “

Thus two distinct types of photography are created, shall we say, one artistic and the other documentary.

This division, however, is often not based on precise patterns while what I would like to achieve is to give schemes almost scientific to differentiate sharply the two sectors. To make this more streamlined lets call the first artistic photography A, while the second, the documentary one B.

As a substantial division lets begin by saying that A is the pure expression of feelings and human passions, while B is a documentation of situations. If someone told me that even in B you could catch a glimpse of the feelings of the author of the photographs, I would answer to these objections by noting that these feelings surely are noticeable and detectable but only by reflection because of the way, the technique in which the photographer has photographed and therefore interpreted the given situation, but it is not a genuine expression, its criticism!

Moving on, we will say that B is the killing of the photographed object (as R. Barthers argues) because it, once photographed and analysed by the viewer, is completely consumed, its function is exhausted.

In A instead of the object is the starting point and thus it is vivification.

As a consequence of these last considerations we also say that A captures the moment in which the object becomes the subject while the B captures the moment in which the subject becomes the object.

In addition, we can also say that A brings out the emotions while B brings about the notions; also A represents situations that are totally unrecognisable and subjective because in this type of photography you photograph not to show others and themselves a something new or lived, but to express personal feelings that need only satisfy the author. In contrast, B represents situations which necessarily must be recognisable and objective.

Another important consideration is that A does not have and should not present a situation as it is, but teases, alludes to trigger in receiver a VERY PERSONAL act of EMOTION. Instead, B does not tease at all but instead it tears decisions, it confronts well-defined facts that in their turn give precise convictions.

On this point, for example, Fulvio Roiter says “photography does not have to refer, nor suggest, it must show with clarity.”

If we now move on a plane of linguistic analysis also in this case we are faced with substantial differences between the two types of photography. First, we say that B is related to extraphotographic factors (language, culture, etc.) that profoundly affect reading, while A contains all morphological units. Therefore it is deduced that A is a unicum, with its own particular code, which is the photograph itself, while in B all photographs of the same sky are tied to a particular code. So we see then a very important thing ie that A is completely universal while b is universal only on a primary level. In A, the only thing you should be aware visually is what is represented in the primary level (for example, a man who has always lived in a cave will never be moved by the picture of a cloud, which he has never seen: in this case takes over the photographic document).

Therefore we can deduce that A is the means of communication while B is a communication system and therefore language (see distinctions of Mounin). And while in A the primary and secondary level are the same, in B they coexist.

We have seen then how diversified the two types of photography are. It is not simple to distinguish them, since it is said that a photograph does not belong to exactly one group or another and I think it is sufficiently useless to analyse it to put a photo in a particular section, albeit intermediate.

However, it is absolutely necessary to make a judgment of this kind with regard to an author, to examine not only one picture but many that if they belong to B they will be linked by a single reading code, while if in A they will be together by a lack of code.

Giving a judgment of value on the two types of doing and understanding photography taken into account may not make much sense, and it is certainly wrong to state categorically that a particular type of photography is better or worse than the other.

But I will not refrain from mentioning a small excerpt from Zibaldone Leopardi: “The present, however it may be, can not be poetic, and the poetic, in one way or another it always finds itself consisting in the distance, in the undefined, in the vague “…

[/en]

rossano

Tema libero “fotografia “…… Praticamente in una botte di ferro !!! 😉

Corrado Chiozzi

Notevole per un adolescente….

Ettone

Concordo con Corrado… Notevole. Al di là della tematica e del pensiero espresso mi chiedo se al giorno d’oggi esista ancora qualche ragazzo che al liceo riesca a scrivere in questo modo a riguardo di un proprio interesse (qualunque esso sia) e non si limiti a scrivere “xé nn so + come si scrive” utilizzando emoticons e abbreviazioni?

E comunque ora capisco perché ho fatto lo Scientifico 🙁 e avevo pure 3 periodico di latino.

Simone

Reitero, notevole: se non altro, per la memoria enciclopedica… 😮

Lela

Sì ma… quanto ti ha dato la Prof per questo super Tema? 😉

Cristiano

Vogliamo conoscere il voto!

…però la calligrafia è orribile 😀

federica

ho un bel ricordo che comprende anche te nel senso che proprio ci passi in mezzo a una immagine che ho della marina il periodo è all’incirca quella del tema tu cammini sul pontile di legno con una macchina fotografica al collo partivi di lì a poco con tuo padre per un giro in barca e sei strafelice

Settimio Benedusi

Il voto non c’é! 🙁

Stefano

Devo assolutamente COSTRINGERE mia figlia ad iscriversi al liceo classico….

Stefano

Aggiungo che dovrebbe essere un voto molto alto, complimenti.

Herbert

Avevi le idee chiare fin da ragazzo. Complimenti per il tema. Come ha detto Ettone è bello sapere che un ragazzo sia appssionato di un qualcosa e lo descriva con amore. Spero che anche il mio bimbo coltivi una passione e la descriva/racconti come hai fatto tu.

Non per parlare per luoghi comuni, nessun indirizzo scolastico apre la mente come un liceo, tu sei la dimostrazione 🙂

Lorenzo

Che dire….per un ragazzo di 17 anni è più che notevole,ma la calligrafia non se po guardà…..

Caro Settimio…..se ti andava male come fotografo,avevi una carriera da dottore assicurata…. 😀

max

Mi sono stampato il tuo tema, tanto è bello. Ma io non sono d’accordo con chi scrive che il liceo apre la mente, ne conosco fin troppi di ottusi che hanno fatto il liceo, e conosco altre menti aperte che han fatto altre scelte, e alcuni non hanno nemmeno potuto studiare.. la mente si “apre” se si è disposti ad aprirla; e ogni tanto serve anche avere la fortuna di incontrare i giusti maestri sul proprio cammino.

Massimo

” … o in un’altro modo” senza apostrofo.